Texte : Alexandre Paul Démétrius Photo DR

Au début des années 2000, le style urbain était incarné par des marques dont les créateurs étaient eux-même issus de la culture street. Ils avaient notamment réussi le tour de force de prendre des parts de marché importantes à des marques traditionnelles, que ce soit dans le luxe, le sport ou le prêt-à -porter.

[mepr-show rules=”8316″ unauth=”message”]

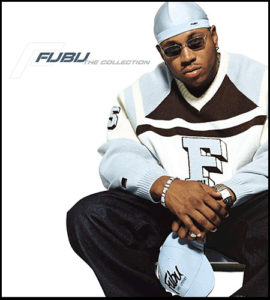

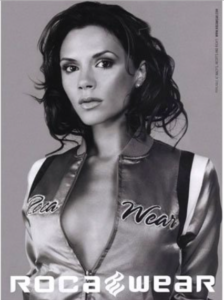

PNB Nation, FJ 560, Ecko, Rocawear, Phat Farm, ou Fubu, aux États-Unis, la fin des années 90 et le début des années 2000 ont particulièrement été marquées par le règne de ses marques dans le paysage des vêtements urbains. A cette époque une multitude d’enseignes occupent le terrain, elles couvrent plusieurs univers qui témoignent des aspirations des 15/25 ans du moment (skate, graffiti, rap etc..), mais ce sont les enseignes fortement associées à la culture Hip Hop et au milieu du rap qui remportent largement la mise, au détriment de marques « Streets » plus confidentielles et élitiste. Leur arrivée sur le marché coïncide avec un constat simple, mais aussi une philosophie entrepreneuriale et culturelles qui s’est désormais perdue.

[emaillocker id=”5111″] [/emaillocker] Le constat ? C’est que les marques traditionnelles de prêt à porter, sportswear, ou de luxe, ne répondent pas aux attentes d’une génération qui plébiscite alors coupes plus larges, graphisme, omniprésence de logos ou d’imprimés et surtout références au monde de la rue incarnées par ses portes paroles : les rappeurs. La philosophie ? C’est le « Do It Yourself ». Au lieu d’attendre que les grandes marques institutionnelles s’intéressent à la population urbaine dans son ensemble, des jeunes créent eux même leurs enseignes, avec aussi l’idée de s’affranchir économiquement et culturellement de l’emprise des gros acteurs de l’industrie vestimentaire. Il faut dire qu’à l’époque et contrairement à aujourd’hui, la plupart des marques institutionnelles quelles soient issues du prêt à porter, du sport, ou du luxe, rejettent la population urbaine jugée trop métissée, sulfureuse, et pas assez fortunée.

Cette erreur d’appréciation va permettre à une multitude d’enseignes d’investir un marché presque vierge et de rencontrer un succès immédiat grâce à un marketing audacieux qui associe les acteurs de la culture urbaine aux vêtements dans les publicités, clips vidéo, représentations publiques etc…

Les rappeurs sont bien entendu en première ligne pour arborer les vêtements, et certains sont même partie prenante dans les marques. Réseaux sociaux et influenceurs n’existent pas et c’est donc à travers les magazines que l’image et l’univers de ses marques se diffusent.

Le succès rencontré par ces dernières génère des millions de dollars et les enseignes traditionnelles commencent sérieusement à tirer la gueule, surtout que les marques urbaines investissent grands magasins, centres commerciaux.. La réaction des grands groupes ne se fait pas attendre, ils rachètent progressivement les enseignes urbaines (PNB Nation, Ecko) à l’exception des plus grandes dans un premier temps, mais ces dernières petit à petit vidées de leur substance, ne rencontrent plus le succès d’avant. Le lien avec les acteurs de la culture urbaine est coupé.

Au fur et à mesure que les acteurs de la culture urbaine sont absorbés par la société, la nécessité de se démarquer économiquement et culturellement s’estompe au profit des marques de vêtements traditionnelles qui réinvestissent un terrain sur lequel elles avaient été challengées.

Aujourd’hui, face à la monté en force du style urbain, plutôt que de se faire déborder par des initiatives qui pourraient échapper à leur contrôle les enseignes institutionnelles de prêt à porter, de sport, ou de luxe, ont préféré intégrer la culture urbaine dans leur communication en récupérant au passage ses acteurs.

Dommage pour les aventuriers de la mode urbaine, qui avaient réussi durant les années 90 et 2000 à inverser le rapport de force à leur avantage.

De nos jours, il reste néanmoins quelques aventuriers de la mode urbaine, et c’est tant mieux pour le street wear, le vrai, l’authentique, celui qui permet à ses acteurs d’en tirer profit.

English :

Text: Alexandre Paul Démétrius

At the beginning of the 2000s, urban style was embodied by brands whose designers were themselves products of street culture. In particular, they had succeeded in taking significant market share from traditional brands, whether in luxury, sports or ready-to-wear.

PNB Nation, FJ 560, Ecko, Rocawear, Phat Farm or Fubu, in the United States, the late 90s and early 2000s were particularly marked by the reign of these brands in the urban clothing landscape. At that time, a multitude of brands occupied the field, covering several universes that reflected the aspirations of the 15/25 year-olds of the time (skateboarding, graffiti, rap, etc.), but it was the brands strongly associated with Hip Hop culture and the rap scene that largely won the day, to the detriment of the more confidential and elitist “Streets” brands. Their arrival on the market coincides with a simple observation, but also an entrepreneurial and cultural philosophy that has now been lost.

The observation? Traditional ready-to-wear, sportswear and luxury brands are failing to meet the expectations of a generation that favors wider cuts, graphic design, the omnipresence of logos and prints and, above all, references to the street world embodied by its spokespeople: rappers. The philosophy? Do It Yourself. Instead of waiting for the big institutional brands to take an interest in the urban population as a whole, young people are creating their own brands, with the idea of freeing themselves economically and culturally from the stranglehold of the big players in the clothing industry. It has to be said that, at the time and unlike today, most institutional brands, whether in the ready-to-wear, sports or luxury sectors, rejected the urban population as too mixed-race, sultry and not wealthy enough.

This misjudgment allowed a multitude of brands to invest in an almost virgin market, and to achieve immediate success thanks to bold marketing that associated urban culture players with clothing in advertisements, video clips, public performances and so on.

Of course, rappers are at the forefront of the clothing industry, and some are even involved in the brands themselves. Social networks and influencers don’t exist, so it’s through magazines that the image and universe of these brands spread.

The success of these brands is generating millions of dollars in sales, and traditional retailers are starting to feel the pinch, especially as urban brands invest in department stores and shopping malls. The reaction of the major groups was swift, as they gradually bought up the urban brands (PNB Nation, Ecko), except for the largest ones at first, but these were gradually emptied of their substance and no longer enjoyed the success they once did. The link with urban culture was severed

As urban culture players are absorbed into society, the need to stand out economically and culturally fades, to the benefit of traditional clothing brands, which are reinvesting a ground on which they had been challenged.

Today, faced with the growing strength of urban style, rather than be overwhelmed by initiatives that might escape their control, institutional ready-to-wear, sports and luxury brands have preferred to integrate urban culture into their communications, while at the same time reclaiming its players.

A pity for the adventurers of urban fashion, who had succeeded during the 90s and 2000s in reversing the balance of power to their advantage.

Today, however, there are still a few adventurers in urban fashion, and that’s all to the good for street wear – the real thing, the authentic thing, the one that allows its players to profit from it.[/mepr-show]